On View

Ever Wonder Why Egyptian Sculptures Are Missing Their Noses? The Answer Will Surprise You

Ancient Egyptian statues were considered a portal to the gods.

You’ve probably noticed that a lot of ancient Egyptian statues have broken noses. Now, for the first time, an exhibition is explaining why. And it’s probably not for the reason you think.

As revealed in “Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt” at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, this recurring damage was no accident, but a targeted destruction motivated by political and religious concerns.

The show is curated by Edward Bleiberg, the Brooklyn Museum’s senior curator of Egyptian, classical and ancient Near Eastern art, and Stephanie Weissberg, an associate curator at the Pulitzer. It features 40 Egyptian artworks on loan from the New York museum, contrasting damaged objects with ones that remain intact.

“The most common question we get at the Brooklyn Museum about the Egyptian collection of art is ‘Why are the noses broken?’” Bleiberg told artnet News. “It seemed like it would be a good idea to actually figure out what the answer is.”

With sculptures this old, it seems natural that there would be some wear and tear, or that noses might shatter when pieces inevitably fall over at some point over the millennia. But 2-D relief works often show the same type of damage to the face, suggesting a deliberate pattern.

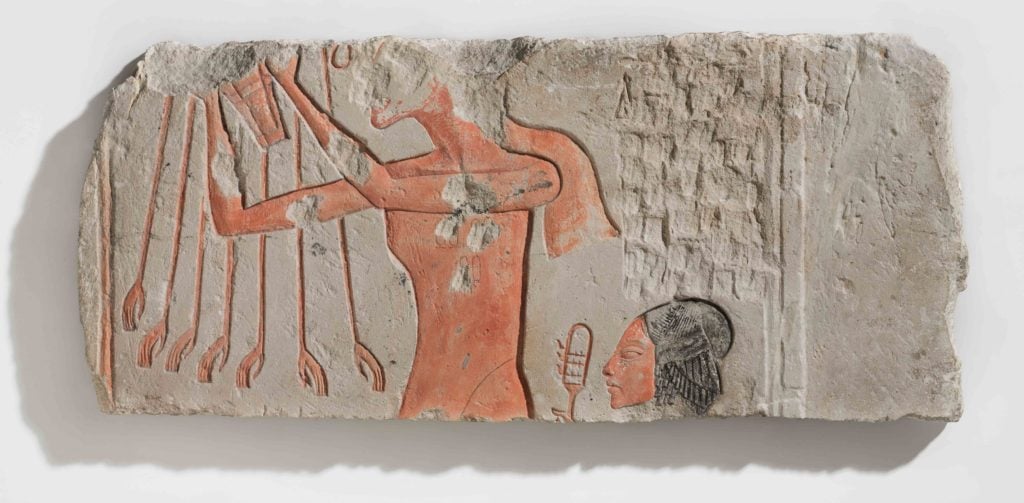

Akhenaten and His Daughter Offering to the Aten. New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, Amarna Period, reign of Akhenaten, circa 1353–1336 BC. Made for a temple in Hermopolis Magna, Egypt. Photo courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund.

As it turns out, Christians and even some pharaohs actually had a habit of vandalizing artwork due to an entrenched culture of iconoclasm. The deliberate destruction of artworks was a way of counteracting the cultural and political power of the image—a world view that resonates across the centuries, as seen in the destruction wrought by ISIS in recent years at ancient historical sites in the Middle East.

“The Egyptians made these images as a resting place for a supernatural being. These are the places where human beings can have direct contact with the gods, or deceased human beings who have been transformed into a divine spirit,” explained Bleiberg. “When they are damaged, it interferes with the communication between the supernatural and people here on earth.”

While one might think that communication with spirits would be desirable, sometimes those who were seeking to concentrate their power wanted the exact opposite—to break it off.

And when you think about how hard these basalt and granite sculptures are, it becomes even more obvious that this defacement was intentional. “These would have been quite difficult to damage,” added Weissberg. “The sheer difficulty and effort involved in making modifications to these works really underscores the urgency and perceived importance of these objects.”